“Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school.”

— Albert Einstein

– – – – – – –

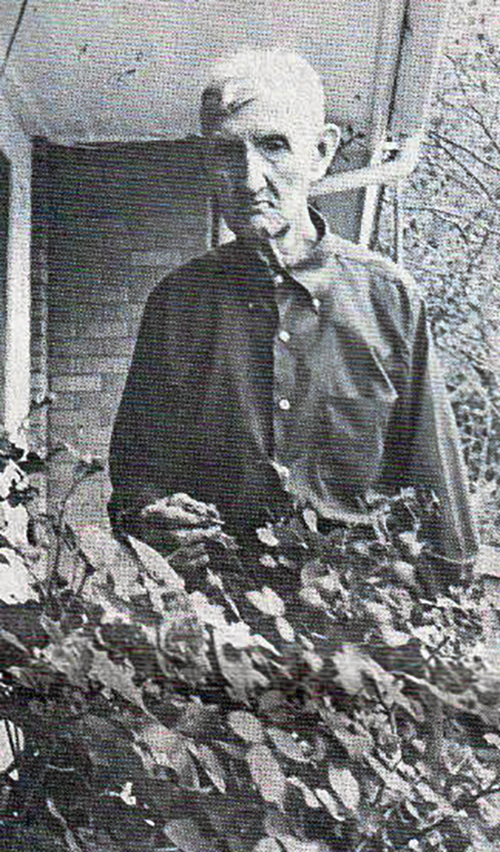

Mom talked fondly about her father. I remember some things about Arthur G. Johnson, my maternal grandfather. He died February 15, 1951. That I can remember him at all seems incredible when I think about it. Considering that I celebrated my third birthday a month before his death.

The most vivid memory is waiting at the bottom of the stairs leading to his second-floor bedroom at 382 South Main in Winchester, Kentucky. Waiting to hear him call my name when he awoke from his nap. That was my signal to sneak up the stairs and hide under a bedroom dresser while he continued calling my name, pretending he couldn’t see me.

Called Pop or sometimes Poppa by Mom and her four siblings, Arthur Johnson was an educated man. Photos picture him as stoic in stature, exhibiting a state of calm and composure—someone that most might expect to face life with education, practicality, and wisdom.

He came from a long line of Kentucky stock documented back into the 1700s. A schoolteacher and a principal in both Kentucky and Tennessee, he also served as an educational director for the Civilian Conservation Corps, commonly referred to as the CCC. Before the U.S. entered World War II in 1941, the CCC constructed public buildings, fences, and state park facilities still in use today; often recognized by their stone construction.

In addition to his educational and professional presence, however, I learned last week that Arthur Johnson also had a penchant for practical applications of learning.

“Let me tell you one story,” my Uncle Bill said last week at the annual reunion of the descendants of Arthur G. and Bernice Conlee Johnson held near Winchester, Kentucky. Uncle Bill is my mother’s last surviving sibling. He celebrated his 90th birthday in May and has always been a great storyteller.

“Pop had a degree in psychology,” Mom’s little brother began. “He was educated and intelligent, but he applied his education with practicality.

“There was a little boy in the neighborhood, also named Billy. And he was … well, he was bad. I mean, he was a really bad seed. His mother couldn’t control him. He got into more kinds of trouble, but she always defended him. He never did anything wrong; you know. It was always the other person.

“At one point, I had a little dog,” Bill continued. “It got caught up in a wire fence around the back yard and couldn’t get out. But this kid killed my dog rather than help it get loose. That’s the kind of evil bad he was.

“One day, his mother comes down the road,” Bill’s story continued. “I’d had a bunch of run-ins with her son. So, when she came flying down the road and turned in at our house, I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, what have I done now?’ That woman was as bad as her son was.”

“’Is Mr. Johnson here,’ she asked me? People in the community often sought Pop’s advice since he was a respected teacher. I told her I’d check; that I didn’t know. So, I went up to his room that was his own world in that house. I told him, ‘Billy’s mom is down there and wants to talk to you.’ He sighed and said, ‘OK, let her in.'”

“She went in, but the door stayed open just a little,” Uncle Bill continued. ” I just stood there, you know, and listened. She started telling Pop about Billy. ‘I just can’t control him anymore,’ she said. ‘He’s mean, he’s out of control, and I don’t know what to do with him.’”

“Pop was quiet for a minute,” Uncle Bill related. “Then he gave Billy’s Mom some advice. ‘I’ll tell you what to do. You go down here to the local library, and you check out a book called Elements of Psychology. Remember that title. It’s a big book. It’s a good book. Check it out and take it home. Then when you get home, you take that book, and you beat his butt with it. Two or three doses of some applied psychology will help straighten him out.”

I laughed. I had always heard that the grandfather I barely got to know was a wise man. One who valued education and the value of a good book.

But I never knew just how well he understood the practical application of them.

—Leon Aldridge

– – – – – – –

Aldridge columns are featured in these publications: The Center Light and Champion, The Mount Pleasant Tribune, the Rosenberg Fort Bend Herald, the Taylor Press, the Alpine Avalanche, the Fort Stockton Pioneer, the Elgin Courier, The Monitor in Naples, and Motor Sports Magazine.

© Leon Aldridge and A Story Worth Telling 2025. Excerpts and links may be used, provided full and clear credit is given to Leon Aldridge and ‘A Story Worth Telling’ with appropriate and specific directions to the original content.