“Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.”

— Leonardo da Vinci (1452 –1519), Renaissance artist and inventor who documented theoretical flying experiments.

– – – – – –

As a licensed pilot, granted one who hasn’t taken the controls of an aircraft in many years, I can still feel da Vinci’s intoxicating longing for flight.

Even as a kid, my young eyes were turned skyward. Dreaming of a day that I might taste the feeling of flight.

That same longing obviously lingered in two little-known, long-ago aviators from Shelby County in East Texas. Their flying adventures were reportedly the subject of family reunion stories for many years—into the 1980s, for sure.

Standing for a long time as a “monument,” of sorts, to their tastes of flight was the abandoned frame of an old airplane in the Southern part of the county known as the Dreka community.

I first saw what was left of the rusty remains in Florence Duncan’s yard on a dirt road some 40 years ago. A stop at Mrs. Duncan’s house, while visiting family friends nearby, introduced me to her and to the fabled stories of the flying machine. Even then, it was already slowly succumbing to grass and weeds.

“It’s been there since ‘bout 1947,” she said of the old airplane’s skeletal parts. “I keep it there for sentimental value.”

“Two of the boys (family members Ernest Duncan and Duncan Rolland) bought the airplane and wanted to turn one of our fields in front of the house into a runway for it,” Mrs. Duncan reminisced. “My husband, Dean, and I told them ‘No.’ But you know what? They cut my persimmon tree and flew it there anyway.”

“It was an old airplane,” she continued. “Duncan said he gave $150 for it.

When they lit it out there that first time, they hit a terrace and broke one of the wheels.

“They fixed it with bailin’ wire before they decided to go to Center in it,” Mrs. Duncan continued. “They came back in a little while, but they didn’t set down on the field quite soon enough. The wheel they wired up didn’t hold, and the airplane crashed, almost flipped over.

“I was scared to death,” Mrs. Duncan recalled. “I went runnin’ out toward the field. The whole family was right behind me. When I got close enough, I heard Ernest say, ‘I told you we should have lit it down in Center.’ That’s when I knew they were all right. I couldn’t believe they crawled out of that airplane and walked away from it.

“After the crash,” she said, “Van Bertherd, a young man just down the road, thought he could do better. He worked on it and headed down to the corn patch with it. The corn was just coming up at the time, and the plane got stuck.

“We wound up havin’ to take the mule down to the field,” Mrs. Duncan continued, “then towed it to a level stretch on the road. Van got it off, just barely clearing the fence and the pine trees, but came right back. Said it needed lots more work.”

According to Mrs. Duncan, the wrecked aircraft was eventually dragged to a corner of the yard where children climbed and played on it. “Pretending to fly,” she said. “I went out there once and asked where they were flyin’. ‘Way up high over Dallas,’ they said.

“Duncan was shaken up for a long time by that wreck , but he admitted later to wishin’ the airplane had been salvaged,” Mrs. Duncan recalled. “Said it would be an antique now, worth a lot more than the $150 he paid for it.”

When I saw it in the 1980s, the wreckage of the Dreka flying machine had reportedly spent years serving as a kid’s playground, target practice, and neglect. By then, little remained but the bare frame, which had once been covered in fabric that had long since rotted away. There were no wings or motor. By appearance, it was a small plane with a cockpit just large enough for a pilot and a passenger in tandem.

A visit to the area last week revealed no trace of the old airframe. I couldn’t even locate Mrs. Duncan’s residence in the heavily forested region. She reportedly passed away in the early 1990s.

I do remember her closing remarks during our visit back then, however.

“I’m glad Duncan and Ernest weren’t hurt in the crash,” she said. Then added, “About the only thing I’m still mad about is my persimmon tree.

“It never did come back.”

—Leon Aldridge

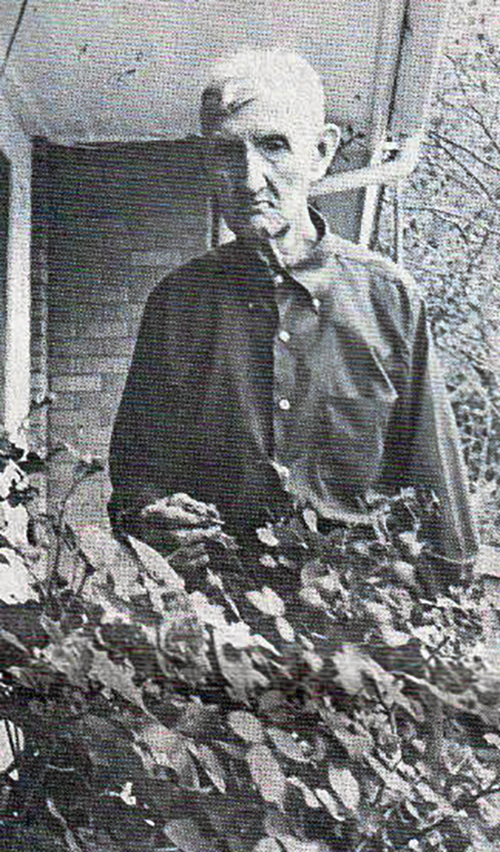

(PHOTO ABOVE — Mrs. Florence Duncan standing next to the Dreka airplane wreckage in her yard about 1981 or ’82. Photo taken by Patricia McCoy, a reporter for the East Texas Light during my first tenure at the newspaper as publisher.)

– – – – – – –

Aldridge columns are featured in these publications: The Center Light and Champion, The Mount Pleasant Tribune, the Rosenberg Fort Bend Herald, the Taylor Press, the Alpine Avalanche, the Fort Stockton Pioneer, the Elgin Courier, The Monitor in Naples, and Motor Sports Magazine.

© Leon Aldridge and A Story Worth Telling 2025. Excerpts and links may be used, provided full and clear credit is given to Leon Aldridge and ‘A Story Worth Telling’ with appropriate and specific directions to the original content.